Review by Colin Clarke & Interview by Marc Medwin

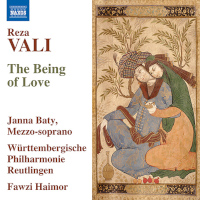

VALI

Ravân. Folk Songs,

Set No. 16:

The Being of Love

1

. Calligraphy

No. 16,

"Isfahan"

•

Fawzi Haimor, cond;

1

Janna Baty (mez); Württemberg P Reutlingen

•

NAXOS 8.579150 (54:43  )

)

I enjoyed two previous releases of music by award-winning Iranian-American composer Reza Vali (b. 1952): a disc of Calligraphies on Albany (Fanfare 40:3) and a follow-up Albany disc in Fanfare 40:5. Another Naxos disc, which included Vali’s Flute Concerto, found its way into Raymond Tuttle’s 2004 Want List (he memorably described Vali’s music by inviting us to “imagine Khachaturian, without the agitprop”).

Written in 2013, the concert-opener Ravân (Flowing) celebrates the 75th birthday of the Pittsburgh composer David Stock (1939–2015); its inspiration is the rivers around that city. It is most appealing, and perfectly fit for its intended purpose. The scoring is deft; particularly delightful are the woodwind pipings followed by sinuous, Iranian-sounding woodwind lines. The performance is expert: Attacks emerge with knife-edge precision, and the orchestra plays with a confidence that implies it has been playing this music for years (which I’m sure is not the case). There are perhaps some Bartókian shadows around the six-minute mark. From jubilant rowdiness to slinky sensuality, Vali fits a whole lot into a mere seven minutes.

The 24-minute song-cycle The Being of Love (2005) is based on Rumi and traditional texts, plus added verses by the composer. I do agree with booklet annotator Frank J. Oteri that there is a verismo element to the drama of the first song, “Longing”; the folkish boisterousness of the second, “Love Drunk,” puts me in mind of Janáček crossed with Stravinsky’s Les noces. It is a lot of fun. Mezzo Janna Baty is superb, both in the extreme emotion of the first song and in the outrageous second one. The third song, “In Memory of a Lost Beloved,” offers a dialogue for one voice between a deceased and a surviving, grieving lover. The vocal line is highly ornate, and Baty negotiates it with seeming ease. Most impressive is the held-breath “The Girl from Shiraz,” a rejection by a woman of a man’s advances. The music freezes, at once sensual yet somehow suspended. Baty’s breath control is magnificent (it needs to be), while the pared-down Württemberg players sustain the mood perfectly, all captured in a brilliant recording. Vali includes references to Wagner (Tristan) and Messiaen (Quatuor pour la fin du temps) in his cycle, but surely the most overt connection is between the fifth song, “The Being of Love,” and the “Azerbaijan Love Song” that closes Berio’s Folksongs; both have a similar sense of kittenish yet sophisticated rhythmic play. Vali’s song is more extended, though; its breadth is an adventure in the mixing of East and West, with instrumental groups layered against each other effectively.

Finally, there comes another of Vali’s Calligraphy pieces, his time No. 16 from 2017. The subtitle is “Isfahan,” and it uses both microtones and Persian modes as its harmonic/melodic basis. (Isfahan is a Persian mode that itself includes microtones as one of its components.) It opens with an extended, high-lying cello solo (uncredited, alas) before expanding out into a properly symphonic canvas of Richard Straussian opulence. The performance is stunning; listening to the microtones on solo strings seems to increase the potency of the resultant sonorities. There are some stunning effects. Strings seem strained to the breaking point in glass-like shrieks around the 13-minute mark; a buzzing bass clarinet sounds almost vocal with notated vibrato. Perhaps Vali’s greatest achievement is to sustain the argument over the 23-minute span via a sonic landscape of great breadth and variety.

Extensive booklet notes take pains to describe what happens in each piece in detail. This is, then, a well-recorded, varied exposition of Reza Vali’s work; all credit is due to the Württembergische Philharmonie players for their clear devotion. Colin Clarke

Union of Contadictory Elements: An Interview with Reza Vali

By

Marc Medwin

“No, my music isn’t really microtonal,” explains the Iranian-American composer Reza Vali. “The concept of a microtone comes from European music. They divide the octave into twelve notes, and anything in between is called a microtone. The Pythagorean system, which I’m using, is based on the pure fifth.” He is elucidating the tuning of Isfahan, the 16th of his Calligraphy series and the concluding track on his new disc, his second in the 21st Century series for Naxos. He explains that in Pythagorean tuning, the upper pitch structures defy the fixed listener experience for those used to equal temperament. He then relents: “But maybe using the term microtone might be better to explain what I’m doing, easier for those most familiar with the European tuning system to understand.” The inclusive nature of Vali’s comment is indicative, and our conversation reveals a constantly questing intellect in search of the unity fostered only by adherence to diversity in practice. The three works on this new disc are performed by the Württembergische Philharmonie Reutlingen under conductor Fawzi Haimor. These works were originally commissioned and premiered by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Manfred Honeck. Composed between 2006 and 2017, they present that questing nature in exquisite and powerful microcosms, continually eschewing expectation until the realization occurs that cultural paradigms have been in play through the entire listening experience. The result is a sort of double exposure, a music both indebted to long-nurtured cultural immersion while existing outside, or just beyond, anything approaching dogmatic association.

There is nothing new about this dialectical approach for Vali. “You know, when I was a child, maybe eleven, I became interested in an accordion that my father bought for my younger brother. He never touched it. It was sitting in a corner, gathering dust. I was too small to hold the instrument properly, so I put it on the floor and began playing it like an organ, pulling it out and pushing it back with my feet. That’s really how I started composing!” The moment was epiphanic, a gateway into an approach that maintains a semblance of familiarity while introducing techniques that stretch the instrument beyond preconceptions. “I never used those buttons; I liked the keyboard! So, you could say that composition came naturally to me, and very early. Later, when I went to the conservatory, of course I had to learn to play the piano, but that early experience was the first to have a profound musical impact.”

For Vali, years of wandering served, in a very fundamental way, to bring him home. In Ulysses, James Joyce elegizes the experience of traveling widely, only to return to meet some altered but recognizable version of the self. An equally appropriate sentiment resides in a quotation from John Updike’s Rabbit Redux: “We contain chords someone else must strike.” Vali’s movement toward integration of his cultural origins was gradual, nonlinear, and something of a community reclamation. “I’ve collected folk music since I was a teenager,” he reminisces. “Wherever I went, I’d acquire records or cassettes. I have so many now, I hardly know what to do with them! However, when I attended the Conservatory of Music in Tehran, we were taught nothing but European music. This was also true when I studied at the Academy of Music in Vienna.” Vali received his Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh in 1985 and soon after joined the faculty at Carnegie Mellon University, where he taught music theory and also ran the electronic music program. He was also composing, but in a decidedly European style seasoned with Persian flavors. It was not until a 1999 trip back to Iran that his long-fostered interest in folk music began to have a major impact on the sound worlds he had already been exploring in his compositions. “I was adapting folk songs in a couple of different ways, using the actual song melodies and composing new material based on folk melodies in the way that Bartók did, but then everything changed.” That 1999 excursion led Vali in a new direction, and over the succeeding years, he imbibed deeply the Iranian Dastgâh/Maqâm modal system and, most importantly, came to a realization of its relationship to the modal system of medieval Europe. Very basically, the Maqâm is akin to a mode, such as the eight modes superficially associated with Greek antiquity that every Western European art music student learns. “The 18th/19th-century European system and the Persian system of tuning are incompatible. However, it was not always the case. In order to understand where the two systems once were conjoined, we have to go back six centuries. The modal system used throughout medieval Europe was not based on equal temperament, and a lot of improvisation occurred in its execution. There was no vertical harmony in the music’s construction, and the dissonances achieved in medieval modality can sound decidedly non-European and strikingly contemporary!”

Vali’s knowledge is as vast as his desire to communicate it is incendiary. Our discussion sweeps broadly over the various power structures that produced the Iranian modal system, the Dastgâh/Maqâm system as we know it today, including the somewhat conjectural third-century AD Dastân system, plus the seventh-century conquering of Iran by Islamic forces and the resultant migration of displaced court musicians, disseminating their traditions over territory from North Africa to Spain. “What happened was very interesting in that an international system evolved, which lasted from the eighth all the way to the 18th century, and that is called the Maqâm system. So, music played in Morocco and music played in Isfahan were derived from a similar system, similar to the way equal temperament was internationalized later on in Europe.” Vali goes on to explain that the seeds of what would eventually become a crisis of intercultural musical identity were planted, one which we are only in the process of recovering, and his own music is a manifestation of that re-merging. “This goes back to my interest in folk music,” he observes. “I realized that no matter how different the Iranian folk tunes I heard might be, no matter which part of the very large country they were from, they are similar, as if they are children of the same mother. Who is that mother? I asked myself. After much research, I realized that the mother of all Iranian music is the Iranian modal system, the Dastgâh-Maqâm system. I started an intensive and constant study of the Dastgâh-Maqâm system. I had to make up for lost time, cramming into a few years what a musician might take decades to learn!” In 2000, he began crafting a system in which the two purportedly different compositional methods are in what might be considered a dialectical state of symbiosis, often employing orchestral instruments in the service of Persian musical concerns. The first pieces composed in this new and evolving system were the initial entries in his Calligraphy series, using only a string quartet at that time. Vali then expanded his aesthetic to include other instruments and ensembles, notably in the eighth installment (Calligraphy No. 8), which necessitates three ensembles and three conductors due to its polyrhythmic and polymetric construction. The series has proven to be a laboratory of sorts, a dialogic workshop in progress, a continually evolving field of experimentation between the composer and a protean ensemble. He even invented software, in collaboration with his colleague Eric Barndollar, to help him learn to hear the necessary intervals and then to teach conventionally trained orchestral musicians how to hear and play them. I respond to Vali’s discourse by admitting that I have very little exposure to Persian music, much less to the systems guiding it. “I’ll show you—let me get my tuning fork.”

It is one thing to listen to a composer discussing process, and another to understand its intricacies, but yet quite another to experience that composer in communion with the music fundamental to his vision. To hear Vali sing Isfahan’s opening cello solo conjures shades of Bartók at the piano or Stravinsky in rehearsal with Cathy Berberian, a deeply personal and even earthy manifestation of a long-nurtured concept. The emotive state at the heart of that solo is revealed as Vali demonstrates the mode itself and what has befallen it in the West. “The mode Isfahan has been turned into the harmonic minor! In European music, and in the Westernized Iranian music of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, Isfahan Maqâm itself certainly is not the harmonic minor; it has a complex structure which is completely different from the harmonic minor. In Persian music, Isfahan is based on two interlocked tetrachords: One tetrachord is Pythagorean and the other is made of natural intervals.”

Of the three pieces on his new disc, Isfahan is the most radical example of Vali’s compositional system in full effect. Named for the Iranian city but also for the mode at the heart of its genesis, the piece presented Vali with an extraordinary challenge. In 2017, the director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Manfred Honeck, commissioned a Jewish, a Christian, and a Muslim composer each to write an orchestral work. “Isfahan proved to be the perfect mode to use! I didn’t want to write a typical opening orchestral piece, and I realized that the balance of Pythagorean and Western tetrachords would be just what I needed!” As the opening cello solo’s motivic material makes its way in various densities and configurations, first through the strings and then the winds and brass, the wisdom of Vali’s decision is made abundantly clear. “String players deal quite naturally with unequal temperament, so they learn this sort of thing very quickly.” As the music rises toward the first large-scale crescendo, culminating in reiterated crashing open fifths, the emotive orchestration in balance with “microtonal” inflections creates a music beholden to and yet beyond genre, geography, and any singular culture.

Ravân exemplifies the other portion of this dialectical continuum. “It means ‘flowing’ in Persian. I was commissioned to write a piece depicting an element, so I chose water. I was thinking about the Youghiogheny River in West Virginia. It’s a wild river, and you can hear the constantly churning rapids in my orchestration!” It is indeed a fascinating mixture of cultural paradigms. The melodies certainly breathe Persian air, and the orchestration is decidedly European, but the various recurrences and rhythmic juxtapositions fit neither into one category nor the other. Vali’s obvious allegiance to melody threatens to eclipse an equally astute gift for harmonic variation, or it might be more complete to suggest that the harmonies spring from the melodies as they chop and churn their micro- and macrocosmically recurrent ways over the constantly morphing and percussion-saturated orchestration.

Being of Love is the new disc’s centerpiece, and also resides at the heart of Vali’s compositional aesthetic. The cycle is about different aspects of love, a perfectly drawn and complex portrait of a state of being in all of its diversity with music to match. “It’s part of my folk song series,” he explains, “and the melodies are folk melodies, but the orchestral parts are in equal temperament.” A single listen through to the five-song cycle reveals that there is much more to the story even than that simplified dichotomy. Notable is the fourth piece, an adaptation of the popular song “Dokhtár Shirâzi” (The Girl from Shiraz). It is a song whose lyrics are decidedly secular, even racy, given that the woman’s occupation is abundantly clear: “These lips are sweet as honey, / but they have a high price. / Come to me in the morning, / because at night / I will not be home.” Despite this, the music is still, evoking an otherworldly ethereality and spirituality through calmly crystalline instrumentation, including delicate percussion. Reinforcing the piece’s mysticism, we hear “Silent Night” at the beginning, and eventually the rising chromatic motive from the Tristan und Isolde prelude enters the texture. Some of the percussion was specially designed for the project. “I wanted wind chimes in E♭ Minor, and I called every wind-chime maker in the USA! Finally, I found someone in Montana who agreed to make them. I’ve had to send these chimes to every place the song cycle was performed, even to Germany for this recording!” By way of complete contrast, the fifth piece in the cycle, the titular piece and by far the longest, draws upon the world of dance, even evoking the controlled rhythmic fire of Brazilian samba in its final section. “I wanted to bring the various aspects of love together, combining the sacred and the secular. The first section is my own poetry, and I envision it as a continuation of the previous piece. The samba rhythms enter with Rumi’s poem, where mountains rise and move to an ecstatic celestial dance.” Not since Messiaen’s final works, a composer to whose vision Vali is also indebted and whom he quotes in Being of Love, have so many and diverse musical types coexisted in such beautiful music. Vali is thrilled with his chosen performers, citing long-nurtured relationships and easy collaboration. “Janna Baty is an absolutely world-class singer! There’s a four-measure section of melismas in “Sogvâreh,” the third song in Being of Love, extremely complicated, and she sings every note just as it’s written!” In February of 2024, Vali recorded five more pieces with the Württembergische Philharmonie, conducted by Fawzi Haimor, hopefully to be released on a future album. As of this writing, Baty will perform two installments of Vali’s folk-songs series, Folk Songs, Set No. 8, and Folk Songs, Set No. 10, on April 20–21, 2024, with the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber Orchestra under the direction of Geoffrey Larson.

Vali retired from his professorial work in 2023, and his schedule remains full. He studies Persian music every day; he has developed an interest in jazz; he is hoping to translate his second book, Introduction to Iranian Polyphony, into English; and of course he continues to compose. “I have another commission from the Pittsburgh Symphony. It is a brief concert piece called The Camel Bell and it will be premiered on June 6, 2025, by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Manfred Honeck. It’s not part of my Calligraphies series, but it does use my Dastgâh-Maqâm-based compositional system in combination with passages in equal temperament.” For Vali, this dialogue of different compositional systems is paramount. “Look,” he emphasizes, “the orchestra needs to be updated. It is essentially a 19th-century formation. One advantage would certainly involve the globalization with which we’re all confronted in the 21st century, but there’s also the fact that equal temperament has outgrown itself. It will only give you a certain number of collections, and I hear these as having been used up by the time of Boulez!” Vali’s explanations bridge the gap between science and aesthetics, taking statistics into consideration alongside an overwhelming desire to combine modes of expression heretofore deemed incompatible. His music is a glorious testimony to the compositional process in transcultural and transgenerational dialectic. “Imagine an international orchestra as being the norm, where instruments from many cultures are heard together!” The temptation to read tones and timbres, toward which Berlioz and Varèse reached, is as irresistible in Vali’s utterance as every sonority and solo flight of fancy he composes. Each gesture captures the optimism of the dance, human and cosmic, the movement of a body in performance or of a mountain in communion with the sky and all that resides beyond.